Dr. Peter Schütt

Rosehips

STORIES AND DRAWINGS

THE REDISCOVERY OF A LITERARY MASTERPIECE AFTER A HUNDRED YEARS

A literary masterpiece to be discovered, rediscovered: a collection of stories penned by Julius Voegtli, a Swiss artist who made a name for himself in the first half of the last century as a painter and urban planner, but who, by the way, was also a talented writer. Voegtli’s book ‘Rosehips, Stories, and Drawings’ was first published in 1923 by the Kradolfer printing house in Biel, his hometown and principal place of activity. However, it was soon forgotten after his death in 1944. Only now has it been rediscovered thanks to the attentiveness of an heir, Hans Vögtli, who has entrusted the cataloging of the estate to the Pashmin Art Gallery in Hamburg.

Voegtli’s ‘Hagebutten’ (Rosehips), named after the home-cooked and rose-scented rosehip jam, the maids’ treat, comprises fifteen ‘Tales and Drawings’ embellished by the author with vignettes at each beginning and end; book illustrations in the French style, literally translated: ‘vine leaves’.

DRAWING ON P. 68 IN 'ROSEHIPS', REFERRING TO THE STORY 'MUTTERSCHAFT' (Motherhood)

The vignette foreshadows gloom. A mother with a worried look, dressed like a maid with a long skirt, bends over her newborn child, who lies not in a cradle but in a mobile laundry basket, as if it should remain hidden. Obviously, it is a child born clandestinely. The picture is gloomy; there is no light coming from anywhere.

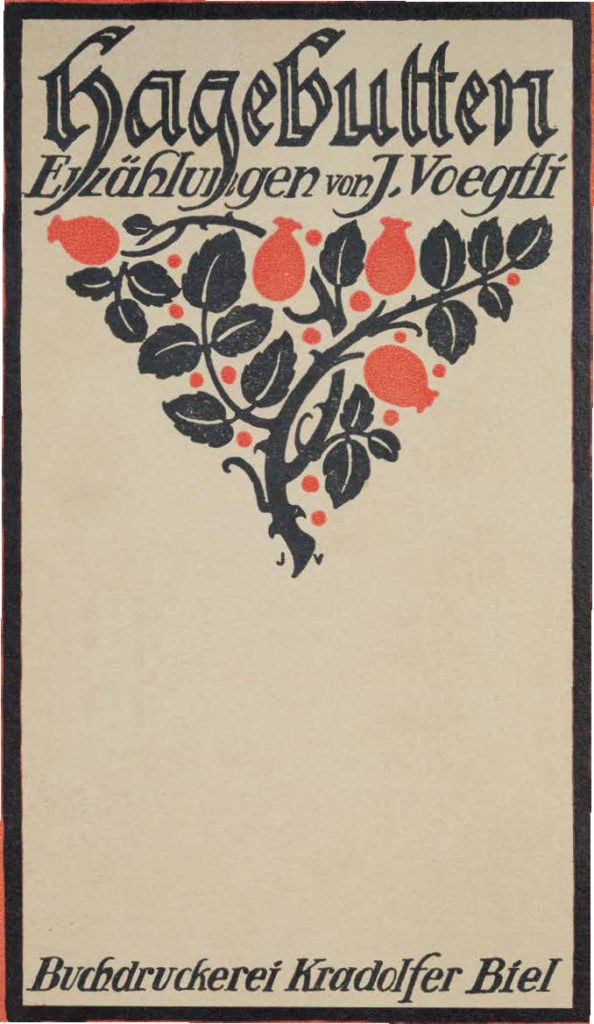

DRAWING ON P. 111 IN 'ROSEHIPS', ACCOMPANYING THE STORY 'HOME'

The vignette that serves as an introduction to the story ‘Home’ depicts a church in the background and the houses of Voegtli’s birth town, Malters. The focus, however, is on a farmer to the right standing next to his cart pulled by two stout cattle. The farmer holds a whip in his hand and on his head – unusual for a farmer – a hat. It suggests that he is a strong-willed person who is stubborn to a fault. However, the apparent village idyll is obviously deceptive. The hero has come to a standstill. He apparently does not seem to be able to separate himself from his village environment and is not sure how to proceed.

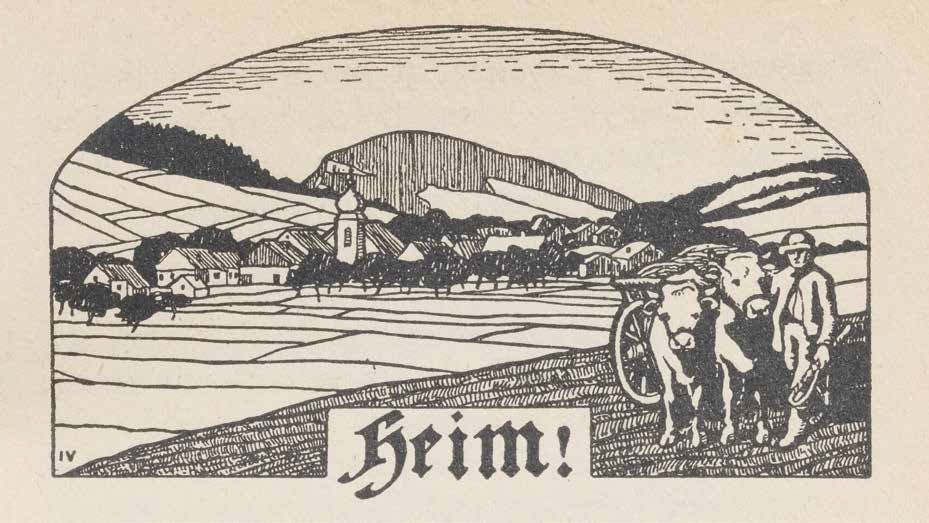

140-7 DRAWING ON P. 60, FROM THE STORY 'MARGARETHE'

Margarethe’s love story ends tragically. The happy bride drowns on a steamboat trip across Lake Biel during her honeymoon. The final vignette, in the shape of a round medallion, depicts the bereaved chaplain bent over the kitchen table. He wears his black cleric gown as if preparing for the funeral service for his drowned young wife. There is no consolation. Nowhere does a light shine. The mourner’s black gown dominates the entire vignette – the antithesis of the opening vignette, which depicts his bride in a flowery white dress.

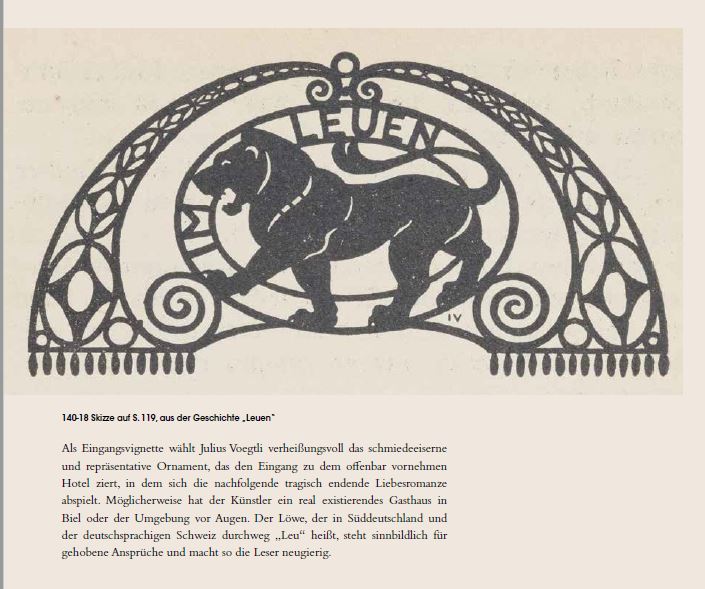

140-18 DRAWING ON P. 119, FROM THE STORY 'LEUEN' (Lion)

As the opening vignette, Julius Voegtli auspiciously chooses the wrought-iron and representative ornament that adorns the entrance to an apparently distinguished hotel where the ensuing, tragically ending romance occurs. Possibly the artist has a particular inn in Biel or the surrounding area in mind. The lion, which is consistently called ‘Leu’ in southern Germany and German-speaking Switzerland, is emblematic of exclusive standards, thereby arousing the reader’s curiosity.

Dr. Peter Schütt

A Heart Aflame

A THEATER PLAY

Julius Voegtli is always good for a surprise, as a painter and an author. Among his most astonishing literary legacies, besides his short story collection ‘Hagebutten’ (Rosehips) also his ‘Bundesfeierspiel’ (Federal Festival) titled ‘Flammen in den Herzen’ (A Heart Aflame) from 1936. It is from his later creative period, which was by this time influenced by the rise of fascism and the growing danger of war. However, for today’s reader, an explanation of this astonishing literary document is necessary. The historical background has become known in the German-speaking world mainly through Friedrich Schiller’s play ‘Wilhelm Tell’. Every year on the First of August, the Swiss national holiday, Swiss citizens commemorate the Rutlischwur, the founding legend of the old Swiss Confederation dating back to 1291. Obviously influenced by Schiller’s drama, it became the national myth of modern Switzerland in the 19th century. Almost all well-known Swiss authors have attempted, often on the behest of the state, to present the legend of the oath of ruthlessness in some form or other, not infrequently as a satirical adaptation. Voegtli’s ‘Bundesfeierspiel’ (Federal Festival) is unquestionably part of this tradition and strictly adheres to the prescribed norms in its form of presentation.